By Elena Botella

Forbes

In November 2019, the Social Security Administration released proposed changes to two programs, Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI). SSDI and SSI are both rooted in a very simple idea: people who can’t work due to an illness, injury, or other form of disability deserve to live, and nobody can live without money for housing, food, and other basic needs.

Under the proposal, some recipients of SSDI and SSI would have to more regularly prove that their medical conditions haven’t improved. Many SSDI and SSI recipients would be required to take part in a more frequent “continuing disability review” (CDR) that some liken to a medical audit for those already shown to be medically disabled. Public comment closed on these changes on January 31 of this year, meaning we can likely expect the rules to be added to the federal register sometime in 2020.

The Social Security Administration explains that they’re trying to make sure benefits stop as soon as recipients have experienced medical improvement. By increasing the number of CDRs they conduct each year by 18%, they expect to spend $2.6 billion less on disability benefits between 2020 and 2029.

But many people with knowledge of the continuing disability review process say the more frequent CDRs will kick people with serious disabilities off of the benefit rolls, instead of identifying people who are now healthy. Since we already conduct CDRs at a cadence grounded in medical evidence, they argue that increasing CDR frequency just imposes an unnecessary burden on the disabled.

“Only a small portion of the people that lose benefits will have medical improvement. The majority will be people who were not able to navigate the bureaucratic hurdles unaided,” says Michelle Spadafore, the senior supervising attorney at the Disability Advocacy Project of New York Legal Assistance Group.

Under current policy, before the proposed CDR changes are made, the Social Security Administration estimates that every $1 spent on CDRs triggers $19.90 in net program savings. By comparison, the more frequent CDRs, according to SSA estimates, would trigger just $1.40 in net program savings per dollar spent on administrative costs, a 14-fold drop in efficiency. “Even by their own calculations, they are going to be harassing people who are unlikely to have medically improved,” says Matthew Cortland, a disabled, chronically ill lawyer.

Why CDRs Cause Disabled Americans To Lose Benefits

“The CDR process is onerous,” says Jennifer Burdick, a supervising attorney at Community Legal Services in Philadelphia, adding that the vast majority of people have to navigate the CDR process without the assistance of a lawyer. When Community Legal Services works with a client on a CDR, it typically takes between twenty and thirty hours, says Burdick, although some cases require up to eighty hours of legal assistance.

The initial paperwork required in a CDR can include up to 15 pages of questions (“It takes two stamps to send it back,” says Burdick). Timely completion of the form poses a particular challenge for recipients whose disability includes difficulty with memory, cognition, or a behavioral health limitation. And that assumes that the recipient even gets the CDR in the mail as they’re supposed to. “I have a client who’s on dialysis, who hasn’t moved, who hasn’t changed her address, but for some reason she never got her CDR paperwork,” says Spadafore. And it’s not uncommon, says Spadafore, for a CDR to arrive when a recipient is hospitalized. If the Social Security Administration can’t make a decision on a CDR due to insufficient evidence, the recipient has only 10 days to request that their benefits be continued while the case gets more scrutiny.

“I’m personally very concerned about the fact that a population that has already established that they have very severe disabilities is being asked to go through the process more frequently,” says Burdick.

Continuing disability reviews typically require the recipient produce new medical records showing that their health status has stayed the same or worsened. A person’s benefits can be terminated if her doctors aren’t timely about sending medical records, or even if the doctor’s notes from appointments weren’t sufficiently detailed. “I have four people on staff whose entire job is hounding [healthcare] providers to submit medical records,” says Burdick.

While the Social Security Administration will also request records on recipient’s behalf, Spadafore says, minor hiccups often derail the process. For example, if a records request is sent to the individual doctor a patient sees, rather than to the hospital where the doctor is practicing, the request will go unanswered, and the Social Security Administration will cut off the recipient’s benefits after making a second attempt to reach the provider, citing a lack of evidence.

In one important way, both Burdick’s clients and Spadafore’s clients are unusual: they found the help of an attorney at a non-profit that provides free legal assistance to low-income people. In a more typical case, Americans with disabilities are navigating the CDR process alone. When they lose their sole source of income, the consequences are dire.

How This Could Impact You, Even If You’re In Good Health Today

While some Americans have lifelong disabilities, debilitating medical conditions often arise in our fifties or sixties, after (and sometimes, as a direct result of) decades of hard work. According to data from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, more than one in four young workers will qualify for Social Security Disability Insurance before reaching the full retirement age. Americans between the ages of 60 and 66 are 14 times as likely to currently be on the SSDI rolls as Americans between the ages of 30 and 34.

Disabilities that first arise in middle age or old age vary. They can include severe carpal tunnel syndrome (which can make it impossible for you to type or work with your hands), debilitating arthritis, cancer, vascular dementia, kidney failure, and fibromyalgia, among a wide range of other conditions.

The bar for receiving SSDI is high: only 23% of applicants are initially approved, and another 12% of applicants are approved on appeal or under reconsideration.

Qualifying and staying qualified for SSDI is extremely important for older Americans with chronic health conditions — even for Americans who worked as white-collar professionals, who might have considerable savings and private disability insurance. That’s because, after a two year waiting period, Americans who receive SSDI also qualify for Medicare, regardless of their age. Without Medicare eligibility, paying for healthcare in your 50s when you’re too sick to work, and no longer have employer-provided health insurance, can be prohibitively expensive.

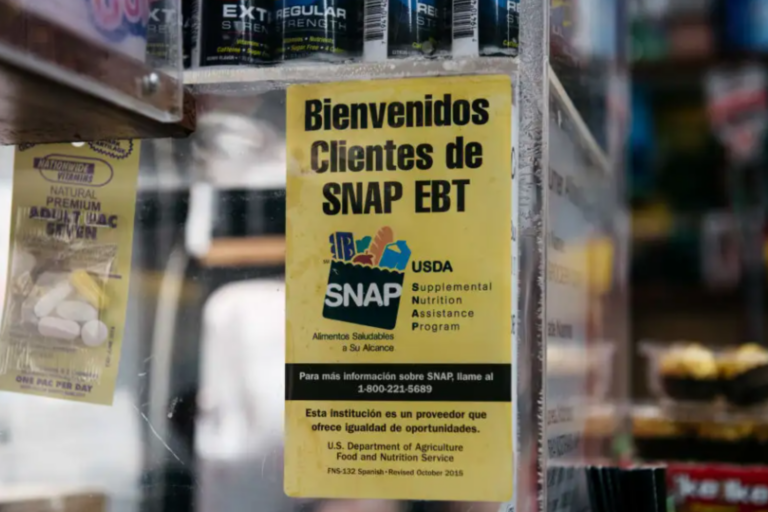

Because Medicare and Medicaid eligibility for people with disabilities is tied to SSDI and SSI respectively, more frequent CDRs will mean some disabled adults also lose their health insurance, a clearly life-threatening proposition. Losing Medicare or Medicaid can mean showing up to a pharmacy and finding that drugs that previously had a $1 copay now cost $1,200.

Older Americans Are Targeted

In the proposed rules, the Social Security Administration highlights a population they plan to target for more frequent CDRs: older Americans who received a “step five” determination of disability. A judge can make “step five” determination of disability if, after reviewing a particular American’s work experience and physical limitations, they conclude that there is strong evidence that person is unemployable.

A typical “step five” recipient might be someone in his 50s or 60s, who worked throughout his life as a construction worker or a janitor. He develops a physical condition that causes him to lose his job. That same physical condition might not make it impossible to work at a computer in an office — but because of his age, and limited education, a judge concludes that employers wouldn’t view the person as qualified for more sedentary work. Judges are only allowed to consider these “vocational factors” — things like a disabled person’s level of education — if the person is 50 or older, a recognition that younger workers face less age discrimination, and have more time to go back to school or gain new qualifications.

As Linda Rothnagel, an attorney at Prairie State Legal Services has written, targeting step five recipients for more frequent CDRs “is troubling and potentially discriminatory, particularly on the basis of age.”

Speaking about the “step five” population specifically, Burdick said, “Most of my clients are getting worse, not better, since you’re adding on age-related problems.” She added that the decision to target these older recipients appears to lack any medical or legal justification.

Death By a Thousand Cuts

Raising the frequency of CDRs is just one example of recent pullbacks to disability insurance. In 2017, the Social Security Administration decided that they would put more weight on the opinions of government-employed doctors, who perform quick evaluations, as opposed to the patient’s own doctors, who have seen the patient’s condition evolve over the course of years. These government-employed doctors, says Cortland, often aren’t in the best position to evaluate a patient’s medical condition, adding as an example that “it’s not uncommon that someone with a gastrointestinal condition gets sent by the Social Security Administration to an orthopedic specialist for their physical.” And now, separate from the CDR proposal, the Trump administration is also considering changes to how older Americans are assessed for disabilities, raising the age at which “vocational factors” can be considered from 50 to 55. President Donald Trump’s 2020 fiscal year budget, proposed in March 2019, suggested cutting $25 billion from Social Security, of which $10 billion would be cut from SSDI, although many of the recommendations Trump made in the budget proposal have not been implemented.

Still, making disabled Americans repeatedly jump through bureaucratic hoops strikes many advocates as particularly punitive. “I can’t stress enough what the consequences will be,” says Spadafore. “I’ve seen a lot of changes come down the pipeline of Social Security over the last decade, and this one is most alarming.”

Originally published in Forbes on February 9, 2020